MC 28 - A Vulgar Theory of Value

“he DID say anus?” murmured someone to my right.

Admittedly, anus is not a word typically associated with corporate governance. Obvious jokes aside, what do butt holes have to do with corporations and the work of boards?

But, on a pleasant October day overlooking London’s Finsbury Circus, the theory proposed by my fellow Australian Graham Logan, that all that was going on in the city below owed it’s existence to the evolution of the anus and poo, provided the gateway into vulgar economics.

Claire Fargeot, Managing Director of Grant Thornton's Governance and Sustainability practice, had invited me to present my novel work on value in use to a select group. The word value, central to corporate governance and the UK governance code, like the word shit, is endlessly spoken about but seldom seriously discussed. Let alone used in the same sentence. That was about to change.

The connection between excrement and value is not new. Apparently the Babylonians thought gold was “the feces of Hell.” “Freud had an idea that in the unconscious mind, that money and perhaps gold in particular, was equivalent to some kind of shit” according to psychoanalyst Steven Poser. There’s even the “shitter of ducats”. A statue of the Dukaten-Scheißer in Goslar, the figure of a little man that apperently produces one coin every 30 seconds.

According to Logan’s theory, life’s complexity may have begun with poop. The Cambrian explosion and sudden burst in the varieties of life traced back to the appearance of the first food consuming, feces-excreting organisms.

Vulgar economics explores similar subject matter - asking whether the evolution of capitalist society was triggered by individuals and firms each producing, exchanging and using the metaphoric equivalent of each others bodily waste or poo - products, services and money?

Vulgar economics is based on a scatalogical or poo theory of value. Proposing that there are similarities between cash, commodities and kaka that are helpful in explaining their production and distribution.

Not that this is a bad thing.

To a vulgar economist, shit is not a pejorative term. Whilst Akerlof may have won a noble prize theorizing the problem of shit cars, vulgar economics focuses on the social side of this social taboo.

In fact, I propose that shit may be the key to understanding how society is provisioned with useful things. The generation of value in use or usefulness, based on the counterintuitive production of the exact opposite - things the producer can’t use - useless waste that must be voided.

Taking an energy perspective, excrement, cash and commodities all share a common characteristic. Each represents the left over energy/value generated through consumption and production that can’t be absorbed by the producer. It becomes a waste product because the energy and value in use is unavailable and inaccessible to the producer. The usefulness of the product can’t be taken in and used by the producer to support its growth. Unable to be put to useful use within the boundaries of the producer, it is useless and becomes unwanted or an “unwant”.

That the “end product” is useful to someone else does not alter the relationship between the producer and its shit. It is the “unwanted” property of money and commodities that makes things available in the market and capitalism possible.

A key tenet of vulgar economics is the existence of an immutable law of supply tied to unwants. A secret and ancient economic organising principle that compels the dispatch of “disposable” products, services and even money to the market in the same way that a bear is compelled by nature to dispatch it’s shit to the woods. What ever the motivation for production, there is a primordial force, identified long ago by Jean Baptiste Say in 1803, that triggers the mutual flow of things from where they are unusable to where they are useful and more likely to be used to perform socially useful work.

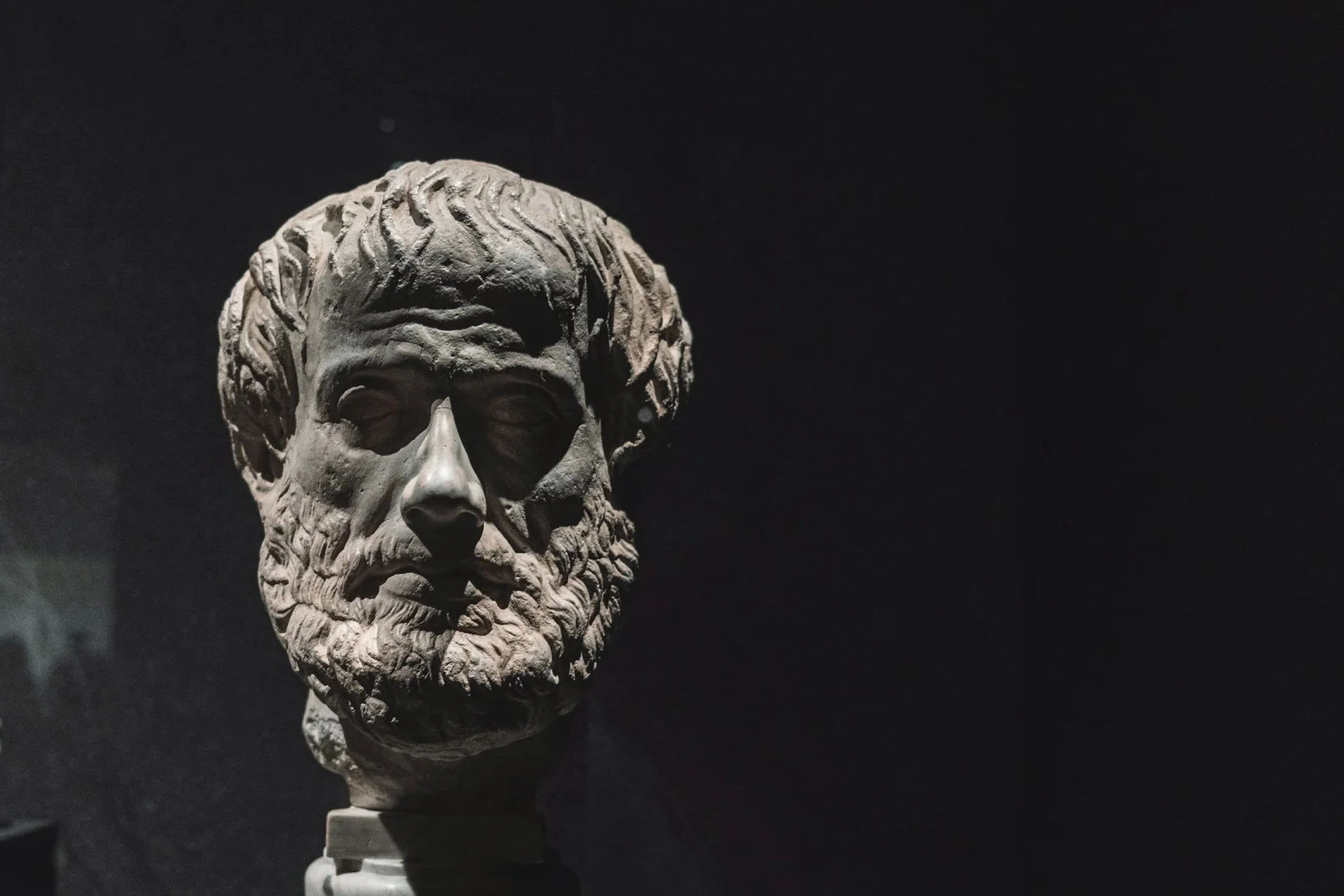

Grounded in Aristotle’s concept of value in use, vulgar economics can also be described as a proto-classical theory of value.

Humanity’s most embarrassing organ and most reviled, worthless and terminal product, the more apt metaphors for the unseen market forces that govern economies and the supply of useful things in it.

Overwhelmed by the urge to purge what they have created but cannot use, producers of commodities and incomes have little choice but to export the unwanted product of their industry in the hope that someone else has done the same, but in reverse. The market bringing the least valued (the unwant or refuse) and the most valued (the want or desire) into the intimate relationship of exchange.

From each producer’s perspective, market exchange operates on the principle of difference and not equivalence as is argued by economists. The less useful something is to the producer, the more value is created for the producer by its dispatch in exchange for something useful. The same applies in the other direction. The differential value in use on either side of the market promoting exchange.

Countless “invisible ani” guided by the “call of nature” drawing individuals and corporations into market relations, which in turn, means that the things that each has no use for, but the other does, flows to where it can be put to use. Mistaken by Adam Smith for a hand, do we have the providential butt hole to thank for capitalism and the virtuous substitution of “end products”?

To illustrate this ingenious mechanism for generating value, consider this question I put to the dealer of the last car I purchased:

I don’t want this much money. How much do you not want that car?

It took a moment for the question to register, but it turns out he didn’t want the car as much as he thought. And far less than the price indicated. In fact, the more I encouraged him to think about it the more desperate he was to rid hemself of it.

In a world of wants, we have forgotten that unwants make the market go around:

Apple doesn’t want it’s latest iPhone, BHP doesn’t want the ore it mines and McKinsey doesn’t want its AI powered “advice”.

No company really wants what it produces. And with pathological exception, no individual really wants to keep their income forever. To each producer their product is as useless to them as scat is to a dog. And much like excrement, it is most useful to the the producer when they are rid of it.

Though unknown to the sanitised, and thus wholly impoverished, neoclassical theory of exchange value, this dirty theorem has the power to explain how value in use is generated and distributed. The never ending need to separate ourselves from our useless shit promoting social purpose through the dissipation of energy in its social form - value in use - without social responsibility or obligation. Society benefiting from the collective imperative to metaphorically poo, more so than the psychology of individual greed.

This is economics returned to the dirt and to its elemental and practical purpose - to realistically explain how societies are continually supplied with all the resources required to live well. The time has long past where economics could concern itself just with the allocation of scarce resource. Allocation being just another word for the substitution between counterparties, it tells us nothing as to whether the exchange of one thing for another left either party ( or the planet) better off.

Not that you will see this entropic mechanism for the socially efficient distribution of usefulness described in any economic textbook. Nor understood, as a potential foundational principle of corporate law and corporate governance.

Attracted to the sterile, linear and methodologically infallible idea that all value is value in exchange, the virtuous similarity between kaka, cash and commodities has long gone unnoticed and unexamined. A decade or more of policy implications waiting to be discovered. We just might be sitting on the key to solving humanities greatest challenges:

in the near term, directly connect global crisis with the universalised practice of taking the exchange of unwants to it’s modern day extreme; and

in the long term, underpin a new value in use theory of the corporation, corporate law and corporate governance. The corporation re-imagined as a social mechanism for redistributing usefulness.

By focusing on demand, wants and equilibrium, I believe economists have missed the fundamental and practical truth that all exchange is based on the double co-incidence of the supply of unwanted things or unwants. In other words, the deliberate manufacturing of disequilibrium. We must all produce things we don’t want or can’t keep, in order for exchange to occur and for capitalism to continue to function. Fated, in the extreme and by excess, to never be satiated by what we produce ourselves and to only be satisfied by consuming the unwanted product of another. A non trivial insight.

A mechanism predicted by Sadi Carnot in 1824. He said that where there is a difference, motive power can be produced. What he could not imagine is that this same principle applied in the markets of Paris as did a heat engine.

Buyers and sellers hacking the second law of thermodynamics understood as a motive force for change. Each deliberately manufacturing their own entropy, in the form of an unwanted baguette and franc, to generate disequilibrium. The pre-requisite condition for market exchange. Exploiting the principle that markets abhor a gradient, the thing that was useless to one flowed to the other where it was useful and could be used and the opposite flow of usefulness in the other direction.

Understood in this way, markets are arguuably based on the faustian principle of each counterparty baiting death to generate life. As far as I’m aware, no other species co-ordinates the manufacture of its own entropy to promote growth. Even if partially true, this mechanism is unimaginable in dark ingenuity and the implications for our undertstanding of markets and capitalism potentially profound.

Though it appears that the mechanism is destined to be received with the same awkward silence reserved for public embarrassment. Confidently ignored based on the impausibility that economists have somehow missed a fundamental mechanism for provisioning society. Let alone, a mechanism inspired by shit and based in biology and the second law of thermodynamics.

But still, a theory of value based on symmetrical disequilbrium is arguably no less implausible than the alternative neoclassical explanation, based on the first law of thermodynamics and psychology. Summed up in this quote attributed to Keynes:

Capitalism is the astounding belief that the most wickedest of men will do the most wickedest of things for the greatest good of everyone.

Next up in the Millennia Challenge I return to the Friedman Paradox, examining why maximising exchange value does not maximise value in use, and consider the implications of making the sole purpose of a company the accumulation of unwants or excremental value in the form of profits.