MC 27: The Friedman Paradox - We Win Some, We Lose More

If there’s a reality that defies economic sense it’s this: if profits are soaring, stock markets are hitting records and global GDP has doubled in the last two decades why is it that social welfare and genuine sustainability, when measured by the accessibility and availability of objectively useful things like, clean air, fertile soil and fresh water, are in decline.

Economists have promised for over half a century that their social purpose through maximum profitability gambit would pay off. Wagering that, absent a host of imperfections:

asymmetric information;

market failure;

externalities;

incomplete contracts;

government regulation;

inefficient property rights,

everyone wins when firms substitute their goods and services for the incomes of individuals inorder to maximise the financial benefits to their shareholders.

And while the eponymous Friedman Doctrine, the idea that the sole social responsibility of a firm is to maximize profits, became the biggest idea in business (The Economist, 2016), was backed in all the way by economists, lawyers and policy makers to become pervasive (Bower and Pain, 2016), became the norm of corporate governance (Macey, 2008) and even considered the law writ large (Bainbridge, 2023), as far as the production of the most socially useful things are concerned, the economic way of life has been more of a crap shoot:

the global temperature is more than 1.5°C above pre-industrial level and predicted to go higher;

90% of arable land is exposed to significant soil degradation;

within my lifetime, wild mammals and freshwater fish have declined by more than half; and

within my children’s lifetime, the same is expected of global insect populations.

Profits are up and useful things are down.

Of course, it’s unfair to lay all the blame on economics. But when the economics profession fell in behind the Friedman Doctrine and took it upon themselves to be the primary discipline that society should use to frame structural decisions on who gets what and why (Van Aartsen, 2024) it is reasonable to expect some level of accountability when their boldest promise is breaking, if not, completely broken.

Not that that defenders of shareholders primacy are close to accepting responsibility or admitting defeat.

Provided the economists preferred definition of value (and value creation) is used as the yardstick- psychological utility without regard to real world usefulness or satisfied preferences as reflected in price – society will always win. When social welfare is measured in terms of what is bought and sold, prices, purchasing power and willingness to pay, shareholder primacy is close to a methodological sure thing. By their personal measure of success, society can’t lose if firms are driven to maximise profits and individuals their preferences.

Untroubled by an objective baseline of the conditions necessary for life, a decline or even collapse in that baseline has little impact on the way economists calculate the odds of success of their social purpose through profit gamble. If more goods and services are being produced, living standards are deemed to be improving even if the standard by which we judge liveability - stability, healthcare, culture and environment, education, and infrastructure are stagnating.

The economists concept of psychological utility adapts perfectly to any loss of value in use or physical usefulness. Their theory of value maintaining its explanatory power despite a reduction of useful things available in the market and largely ignoring what is happening outside the market as an “externality”. The "facts" hold true for economics irrespective of a declining or degrading baseline. It’s why economists “commonly prefer objective empirical evidence over unverifiable reports of affected individuals” (Bebchuk, 2013).

The fact don’t lie. But maybe the theory does.

By sticking to the evidence that fits their economic model, the house that Friedman built will always win despite being unable to address the most significant scientific, political, social environmental problems of the 21st century:

Why does maximising profits for a firm’s shareholders while operating within the bounds of open and free competition, without deception not also increase social welfare when measured in terms of the availability and accessibility of socially useful things.

How can useful things be in decline in the world if the market is so good, just, powerful and efficient?

If markets are the best way to organise society why is it that the things with the greatest price cannot buy the things with the greatest value in use? All the diamonds ever mined unable to reacquire a fraction of the seas, rivers, lakes, and aquifers dried up, diverted, poisoned and polluted in the pursuit of profit and things with exchange value. Why can’t firms, so proficient in producing exchange value, produce and reproduce the things required for life, let alone a good life?

This essay considers what I call the the “Friedman Paradox” - If markets are so perfect, why is there so much uselessness in the world?

Society Wins Some, But Loses More

The essence of the Friedman Paradox is the notion that under the conditions of the Friedman Doctrine society wins some but loses more (and perhaps even all). A profoundly simple idea captured in two diagrams released in weeks of each other.

The first was produced by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, when awarding the 2025 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences to three economists working in the field of “innovation-driven economic growth”.

The illustration making the point that “economic growth has lifted billions of people out of poverty over the past two centuries”. The academy going on to state that “while we take this as normal, it is actually very unusual in the broad sweep of history.”

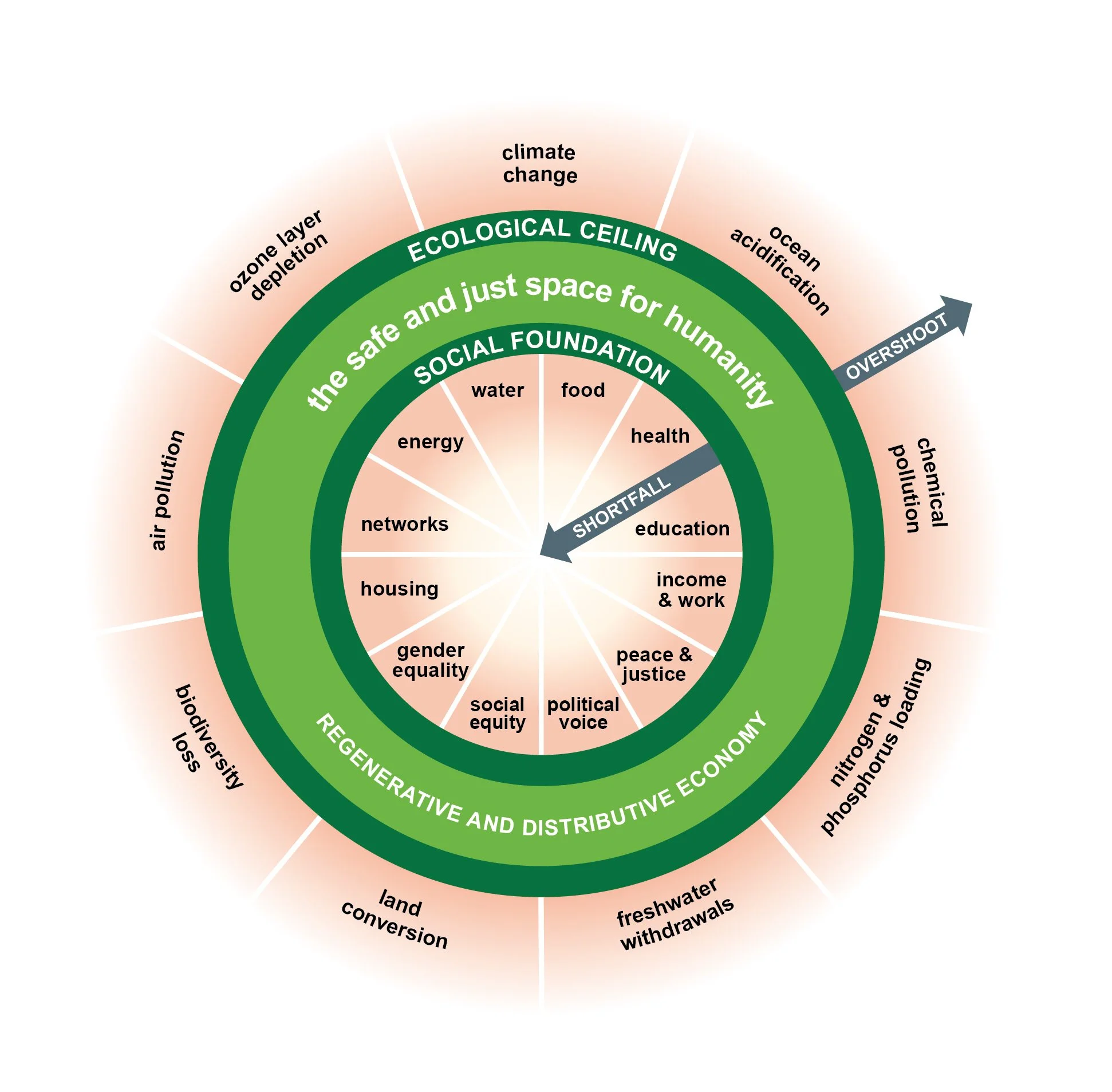

The second, diagram expresses something so unusual in the “broad sweep of history” that it has never happened before. Humanity piecing the boundaries of liveability. The ultimate expression of a vain and uselessness endeavour.

Produced by Andrew Fanning and Kate Raworth when presenting their revised Doughnut framework, sets out 35 indicators that monitor trends in social deprivation and ecological overshoot over the last two decades.

If the period since around 1800 is the first in human history when there has been sustained economic growth, the period since 2000 is the first in human history where so many of the planetary boundaries have been transgressed. We win some, but lose more.

The purpose of this essay and the next, is not to prove or establish causation between economic growth and the shrinking space in which life thrives. That is the role for scholars and science.

This and the next essay asks, if the goal of economic science is to improve the ever day living conditions of people in their every day lives by increasing GDP and incomes (Samuelson and Norhause,1998), why are the lives of everyday people now at existential risk. Put simply, I ask why don’t firms produce the things that are most useful to those people? The variety of things that everyday people need in order to grow.

The Friedman Doctrine

The Friedman Doctrine is founded on that the assumption that if companies make the most money, it is for others to exercise their right and freedom to spend their money for their own purposes:

Insofar as [a business executive's] actions in accord with his "social responsibility" reduce returns to stockholders, he is spending their money. Insofar as his actions raise the price to customers, he is spending the customers' money. Insofar as his actions lower the wages of some employees, he is spending their money.

The Nobel prize winner going on to argue that the appropriate agents of social causes are individuals:

"The stockholders or the customers or the employees could separately spend their own money on the particular action if they wished to do so."

Implicit in this framing is the idea that the social welfare is the product of the purchasing preferences of free individual shareholders and other stakeholders.

“There are no “social” values, no “social” responsibilities in any sense other than the shared values and responsibilities of individuals. Society is a collection of individuals and of the various groups they voluntarily form.

In other words, the best of all possible worlds is that which we are prepared to pay for individually and collectively. A world free of the values of the best intentions of ideological politicians or the worst intentions of fundamentally untrustworthy executives. If the price is right, money can buy everything, including sustainability. It follows that a society can never have too much money.

Leading Friedman to conclude his famous article 1970 article:

“in a free society, and have said that in such a society, “there is one and only one social responsibility of business—to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception or fraud.”

A message that has been embraced as the central organising principle of the corporation and corporate governance. Making financial value as the mission, reflected in their governance structures and one-dimensional accountability to the financial success of shareholders ( Jensen and Meckling,1976 and Fama, 1980).

The Friedman Paradox

Born a year before the famous New York Times article in which the economics professor made his argument, I’ve grown up with the Friedman Doctrine, worked within the set of behaviours it embedded within the firms that I have acted for, from performance measurement and executive compensation to shareholder rights, the role of directors, and corporate responsibility ( Bower and Paine, 2016), and been witness to every overshoot of the planetary boundaries ( Fanning and Raworth, 2025).

Over the course of my life profit maximization has come to be conveyed as a kind of natural law of economics or as a scientific, even pseudo-religious truth (Orts, 2024). Yet, at the same time as global GDP was doubling, the “Planetary Health Check 2025”, is warning that humanity was exceeding seven of nine planetary boundaries.

If the earth’s life support systems are a proxy for social welfare (and they are), we have a Friedman Paradox[1]:

Why does maximising profits for a firm’s shareholders while operating within the bounds of open and free competition, without deception not increase social welfare when measured in terms of the availability and accessibility of socially useful things

Paradoxes can be useful. Management scientists and psychologists agree that the tension created by opposing ideas creates tension that leads to a breaking down of assumptions and offering a new way to look at problems.

For example, when I reflect on the Friedman Paradox I am drawn to four questions:

Why the f### does anyone think that money can buy the highest possible level of welfare.

Who the f### would think that the most useful thing a corporation could do for society is to make as much money as possible as algorithmically possible.

Where the f### did economists study law. Butchering agency and corporate law to fit their loaded principles and assumptions.

When the f### will we stop listening to such patently absurd nonsense.

Make no mistake there’s a use case for money and it’s useful but it’s not, as one billionaire many times over seems to think, magical:

“You could solve every problem in society if you get to 4 per cent GDP Growth”

In the real world of dirt, bugs, overheating oceans and smog, we simply can’t buy back the world that in some way or another has been substituted for products, services and incomes.

GDP per person can’t buy all that is destroyed in the production of money. Put simply, a great many useful and socially necessary things destroyed in the production of profits are not produced by the market and therefore unavailable to be purchased with any amount of money. All the market can do is offer a poor substitute. Meaning not only have we lost the socially necessary thing, but our socially useful incomes are now diverted to buying that which were once both superior and free.

GDP per person can only buy that which the producer doesn’t want. If it’s socially useful but the producer doesn’t want to give it up, it’s unavailable to solve society’s problems. For example, if corporation and the 1 % are analy retentive and want to hoard trillions of dollars that they can never use, none of that is available on the market to do socially useful work. The purpose of the market is to enable unused but useful things to flow to where they are used and useful. The market fails when firms and individuals accumulate useful but unused things rendering them useless.

GDP per person can only buy what is available in the market. What’s the use of increasing GDP per person if a person is compelled, by the lack of inherent usefulness of money, to spend it on a great many things that are either not used, useless or not as useful as things that are not available on the market or produced by firms. And usefulness and social necessity, playing no part in the production decision (Polyani, 1944) what hope is there that the useful and socially necessary things destroyed will be substituted with anything that comes close. Let alone, see the production of things that are more useful than the hours spent acquiring the money to pay for them.

The irony is that in searching to make economics value free in the image of the natural sciences, Friedman had managed to create a “science free” economics. Though clothed in the mathematical pretence of science, this version of economics is largely unscientific. Unburdened by the biophysical implications of profit maximization and the limitations of money as the primary, or even sole means to achieve social ends, economics had become as detached from the planet in the 21st Century as astronomy was from the universe in the 16th Century.

The implications of a science free economics lost on the supremely confident Friedman, who concluded his Nobel speech by impressing upon his audience the importance for humanity of a correct understanding of positive (values free) economic science by quoting Pierre S. du Pont:

“Gentlemen, it is a disagreeable custom to which one is too easily led by the harshness of the discussions, to assume evil intentions. It is necessary to be gracious as to intentions; one should believe them good, and apparently they are; but we do not have to be gracious at all to inconsistent logic or to absurd reasoning. Bad logicians have committed more involuntary crimes than bad men have done intentionally” (25 September 1790)

What was Friedman’s crime?

The ultimate failure of markets. A situation in which firms, driven to maximise profits, substitute socially necessary and useful things with socially unnecessary and use less or unused things. A paradox in which markets increase the production of exchange value but decrease the production and (reproduction) of the value in use required to do socially productive work.

Ecodicy – In defence of the Friedman Doctrine

Ecodicy is the attempt by economists to resolve the “problem of uselessness” ( a more direct expression of the concept of unsustainablity) by reconciling the belief that markets are efficient, just and powerful with the decline in useful things in the world. It combines the Greek word “oikos" (meaning "house" from which we get eco in economics) and “dikaios (justification).

As far as I can reason, there are three versions of ecodicy used by economists to explain the absence of useful things in the world, the strong, the moderate and the new believers.

The Strong Version - The Best of All Possible Worlds

For Friedman, on the modern map of human progress social welfare was marked as the point where the preference maximizing demand curve intersected the profit maximizing supply curve. X marks the spot where free will meets the free market. Everything else is nothing but a woke expression of contestable values rather than incontestable value.

To the most ardent defenders of shareholder primacy, the notion of a Friedman Paradox is nothing more than the hand ringing or a poor loser.

If the shoppers of the world have freely bought their preference and the firms of the worlds have freely maximized the most profit, this version of the planet, is “the best of all possible worlds” when compared to all other alternatives. The divine providence of the invisible hand revealed by the market at the intersection of profit driven supply and preference driven demand.

The Moderate Version - The Market Works in Mysterious Ways

To the more moderate defenders, people like Alex Edmans and Colin Mayer, the Friedman Paradox might be considered nothing more than a timing issue.

Markets are imperfect and the role of the economist is design interventions that address market failures. In the inevitable march towards perfection, some level of market failure is to be expected.

The moderate version has two main arguements:

in time, the Friedman Paradox will be resolved through market-based mechanisms, better legislation, disclosure and regulation, improved corporate governance, ESG and the correct incentives; and

It’s possible to buy our way back into the planetary boundaries buy purchasing sustainable goods and services.

In other words, what separates the Friedman Paradox from the promise of the Friedman Doctrine is money. And firms are having a crack at it; $7 hundred thousand per corporation on ESG disclosure; $2 Billion on ESG Data,;$50 billion on ESG consulting, $40 trillion on ESG investments.

The New Believers - The Second Coming of Steve Jobs

The third form of ecodicy and perhaps the last line of defence, is that the Friedman Paradox will be resolved by something between the rapture and the second coming.

Since the publication of the limits to growth in 1972, that warned that unfettered economic growth could lead to the collapse in global society by 2050, economist have put their faith in innovation and technology to save us if their theory can’t.

At the 2025 International Corporate Governance Societies conference this year, the keynote argued that corporate governance must evolve to creating long term value for the world. When I questioned whether the problem was that the world was butting up against the limitations of the neoclassical theory of economics (and corporate governance) her response was not to defend economics (she is a finance professor) but that she drew on her faith in innovation and technology to maintain her optimism in the future. A deeply unsettling conclusion to what up till then had been a perfectly reasoned presentation.

I don’t buy any of it. And neither should you.

The Longest Shot

I have neither the patience to accept my lot in this collective life nor the risk tolerance to wait and see if the market works its way out of the Friedman Paradox or the second coming of Steve Jobs ? My bet lies else here and whilst the odds are the longest imaginable, and I’m only investing thousands and not trillions, you can’t win without a horse in the race.

Next up in the Millennium Challenge, I dig deep into the Friedman Paradox to explain why the Friedman Doctrine and the idea of maximizing profit will never resolve the problem of usefulness. Largely because maximizing profit is logically a primary cause of uselessness in the world.

Admittedly, my argument being based in the protoclassical concept of value in use, will be the longest shot.

The notion that the Friedman Paradox might one day be as well-known and considered as the Friedman Doctrine is improbable for at least three reasons that have nothing to do with the logic or argument.

First, in Australian betting parlance, the idea of the Friedman Paradox getting up is a roughie. An outsider with no chance of success. In a race between theories of value, value in use would be named Quixote. Leaving aside my absence of any economic pedigree, my work is could best be described quixotic. In the 21st century, practical reasoning from first principles, is not that dissimilar to chivalry in the early 17th century. Past their use by date, both ideas, once considered useful to society, became useless and unused. And those who thought them still useful and practical, easily dismissed as fools like the Man from La Mancha.

Second, being grounded in the largely forgotten concept of value in use, vulgar economics sits outside both orthodox and heterodox economics and is unlikely to resonate on either side of the economic divide. Those who argue for social purpose through social responsibility (stakeholder theories) and those argue for social purpose through profitability (shareholder theories) generally agree on the definition of value but disagree on the best way to distribute it. My response to the Friedman Paradox being based in an entirely different and unfamiliar theory of value is therefore most likely as incoherent to Alex Edmans as it is to Colin Mayer. Likewise, however useful it is to live within the boundaries of a Raworth Doughnut, it all radiates from the central assumptions of neoclassical economics. It is a map in which the compass points in the direction of the economic equivalent of the north star. The three P’s - profit, preferences and prices.

Finally, it should not be expected that my argument will be received well (if at all). The risk of letting vulgar economics run is that even forgetting the impossible improbability, the materiality is such that the house that Friedman built could go bust. This is because a value in use critique of the Friedman Doctrine threatens one half of the foundational idea of supply and demand. If firms have welfare interest measured in value in use rather than exchange value the logic of the supply side of their equation vanishes. So too the foundations of theory of the firm and corporate governance that arose out of the same axioms. Of course, it does not follow that this would be the end of the profit making firm, but I don’t think anyone is prepared to bet on that.

[1] And I’m just the last person to use the phrase Friedman Paradox. Friedman himself using it in a 1972 paper in which he observed the paradoxical relationship between Jewish intellectual’s hostile to capitalism despite the benefits. More recently employed to describe idea that one can't maximize shareholder value without maximizing stakeholder value to