MC22: The Great Collapse and its Antecedents or The Black Swan too Big to See

The essence of usefulness is change. Without useful things, change is something that tends to be experienced negatively rather than being positively made. A useful thing produces good change.

But what constitutes good change?

Good means what Benedict De Spinoza meant. In Ethics, published in 1677 shortly after his death, Spinoza defines good in terms of usefulness:

By good I shall understand what we certainly know to be useful to us.

Ethics, Part IV , Def

In modern value theory, if a thing is accessible and available to a system (social, natural or otherwise) to do the work of social change it’s likely to be good and useful. This property, when applied in physics to formally represent the energy available to do the work is represented by phi Φ (Chaisson 2001). A convention adopted in Modern Value Theory.

Conversely, if something can't produce good change it's not that useful. It’s the opposite of value in use. Polyani, identified this property and called it counter-value. But it's also called antivalue (Harvey, 2018) and I recall someone called it unvalue (but I can’t remember who). You probably know it as a “negative externality”.

Modern Value theory adopts the expression Counter-value. Mostly because I read Polyani before Harvey. Regardless of the name, the most important property of counter value is that it can be “infinitely bad” ( Harvey).

When a language is forgotten or deliberately destroyed it’s infinitely bad because all the useful knowledge coded in that language ceases to become available. Though, counter-value is not something you want to dwell on for too long as you’ll find yourself trying to avoid killing even the most annoying fly. When we mess with life all the sliding doors close. But forget I mentioned it. The two points to take away from the concept of counter value are, no good comes from counter-value and no price can be put on the infinitely bad.

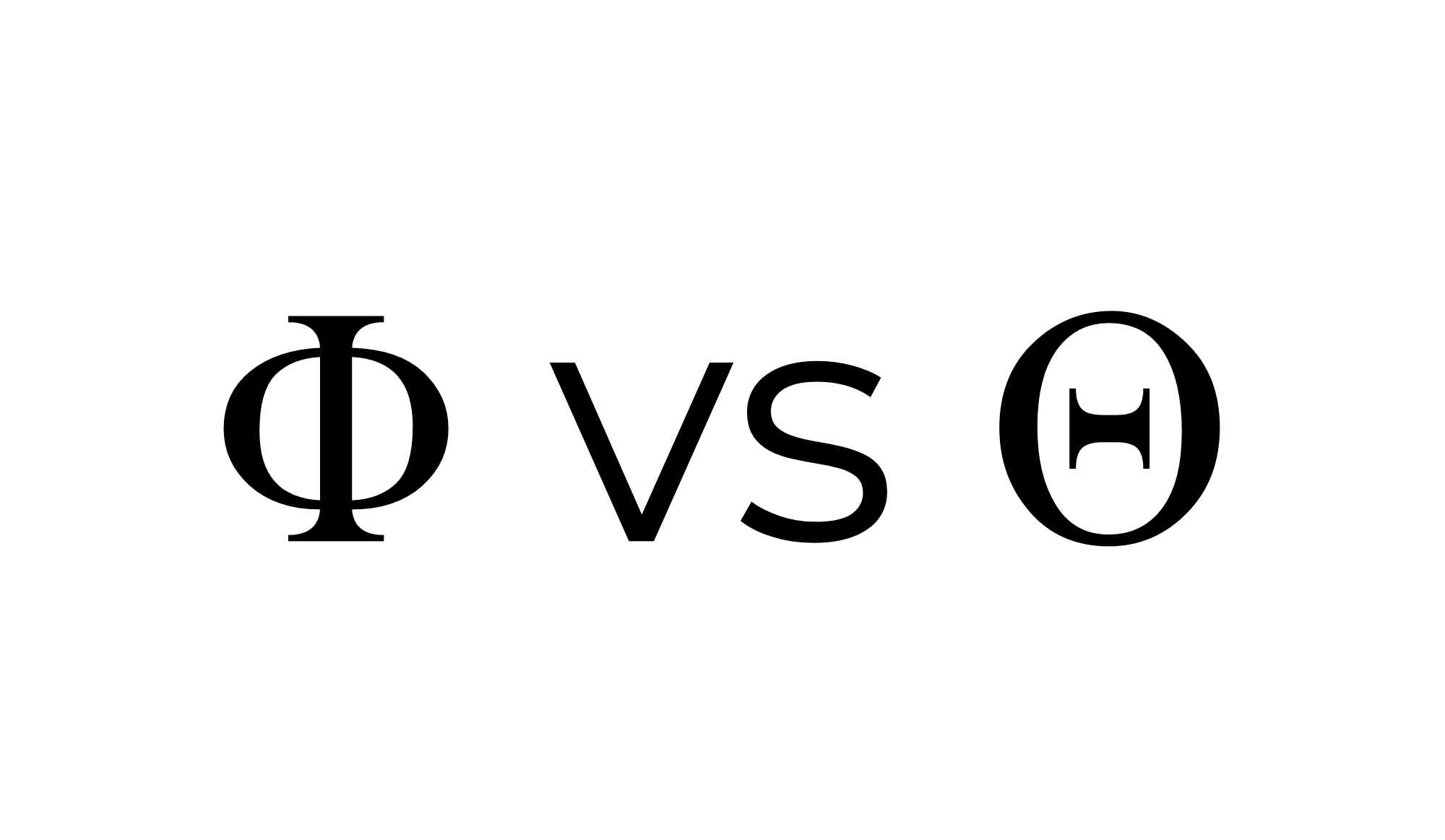

If value in use is meaningfully represented by a circle with a vertical line - Φ - the obvious meaningless symbol for counter-value would be a circle with a horizontal line - Θ. But it turns out that theta is as equally a meaningful representation of counter-value as phi is to value in use.

Called the theta nigrum or black theta, the symbol Θ can clearly be seen in the mosaic below indicating that the gladiators had not passed out after a big night but were in fact dead. Death being the one thing we know with almost universal certainty is not useful to us.

A good introduction to the idea of counte-value is to think of Thanos, the evil villain of the Marvel universe. Whose name (perhaps not co-incidentally) looks a lot like Thanatos who the was the personification of death in ancient Greece.

Counter-value is the core premise of Avengers: Infinity War. At the end of the movie, while wearing the Infinity Gauntlet, the “evil” warlord Thanos clicks his fingers and wipes out half the planet's human capital. A world of less people and a future without everything useful they might have done.

The battle between value and counter value another way to think about good and evil. And, by evil I mean what Spinoza meant:

By evil, however,I understand what we certainly know prevents us being masters of some good.

Ethics, Part IV , Def2

The Great Collapse and Its Antecedents

In MC22 I started a list of useful things that are in serious decline. In fact, it’s no exaggeration to say that the planet has experienced what can be described as a collapse in useful things in the last 50 years. The number and variety of things available and accessible to do the work of flourishing are in decline and counter-values are in the ascendancy. We have a lot more stuff but we can do less with it.

This is a concerning for two main reasons:

when there's more counter-value in a social system than value in use, crises tend to form; and

once a crisis forms, our choices depend almost entirely on the value in use that’s available and accessible to that system that can be transformed into change.

Leaving aside telekinesis or the popular management idea that a change of mind and purpose is the primary way to influence physical systems, the obvious solution to a great collapse would be to start producing more value in use. A new era marked by the great supply of useful things and life.

But that's a monumental challenge for any society that relies on the idea of exchange value for the production and supply of its things. That is, the belief in the idea that things get produced at the intersection of supply motivated by firm profits and demand motivated by individual preferences. In short, what gets bought is what gets made.

However, under this model of capitalism, the business of business was never intended to produce useful things. Rather the system is explicitly designed to produce value in exchange, ignore the production of value in use and treat the production of counter value as a problem for the legal system to resolve (but curiously not corporate law). If value in use is created and supplied it’s more by accident than by management intent.

This notion might seem counter-intuitive or even foolish. After all, if things were not useful they would not be bought. But likewise, if consumer preferences were a proxy for real world usefulness there would never be a crisis of useful things. It’s quite the paradox.

The reality is that there’s a tenuous relationship between supply and usefulness. First, suppliers have long put all their weight on the demand side of the scale - (it’s called marketing among other strategies). Second, and more importantly, under a supply vs demand model, usefulness is a marginal quality of a thing. To the extent something is useful, it just needs to be a little more useful than something else in the market including their own products (the increments of a unit of 1 built into the branding - the galaxy s24 or the iPhone 15). The world of useful things is not measured by the bounds of imagination but constrained within the meek boundaries of profitability. Third, it’s important to remember that the enterprise called nature does not supply according to demand for lower temperatures, fewer droughts, fresh water or more insects.

It’s no coincidence that, in the same time that it's taken for the all pervasive economic style of reasoning to take hold, the planet has gone from brimming with useful things to running closer to empty. And with it, the capacity to change when confronted with crisis. And though it's impossible to deny that a great many useful things have come in and out of existence in that time, past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

The Black Swan too Big to See

The most obvious reason for the great collapse is that modern economies were not designed with the objective of supplying useful things. Lots of things - yes. Useful things - if we’re lucky.

By insisting that the purpose of business and corporations was to make the greatest profit (even within social and legal constraints) (and hyper efficiency for governments ) economists had, more or less, guaranteed a future with less useful things. Profit driven supply vs preference driven demand turns out to be recipe for less value in use and more counter value:

By ensuring that the supply of useful things was not the responsibility of business. In theoretical economics, the real world usefulness of things plays surprisingly little to no part in the production decision. Supply decisions are a question of weighing the economic costs and benefits.

By ignoring the useful things destroyed in the process of supplying things that generate a profit. If counter value is generated outside boundaries of the firm they’re not included in production equation. Instead they're called “negative externalities”. A “cost” that the firm does not have to carry or attenuate for. But counter values are not really costs. There is no market for useful things that no longer exist. And no one can be compensated for that which can't be bought in the market. There is only a void in which to pointlessly throw money.

By nominalising the firm and treating the concept interest and profit/shareholder value synonymously. Under the standard economic model, firms can have no welfare interests of their own other than eventual profit. Production decision, like the supply decision are a question of weighing the economic costs and benefits that again theoretically neglect considerations of value in use vs counter value within the firm. Firm's end up with more profits but are starved of more useful things - social license, sustainable suppliers, new ideas etc.

By vocationalising learning. Education has shifted from the supply of individuals that are useful to themselves and society in the broadest sense to a very narrow concept of usefulness in the pursuit of profit.

By promoting firms that create little to no value in use (the financial services industry) or, in a net calculation, dangerous counter value (fossil fuel companies, weapons manufactures and social media companies) have increased over the past 50 years.

By reducing the impact of government. Institutions that once inefficiently produced useful things, now efficiently produce less useful things. Through a combination of privatization and the widespread adoption of the economic style of reasoning, it often seems that the production of useful things has ceased to be the role of government.

Whatever the moral and ethical arguments against the profit-maximizing objective of the corporation (and efficiency for government), there is a practical flaw with the economist's supply vs demand reasoning. When the production of things is motivated by profit maximization:

more things are supplied but their usefulness is almost accidental;

useful things tend to cease to exist; and

counter values or the things that can't produce good change start to out "number" values in use or the things that can produce "good change".

It may have taken a few decades but the collapse in value in use is happening across a class of things which are not just useful to humanity but are also existentially useful - biodiversity, food, accessible and available clean water and air, a climate compatible with life. All recorded in the alternative scientific sets of accounts.

To be clear, my criticism of the economic style of reasoning is not a normative one. It's not a question of ought or ought not. I’ve just followed a kind of old fashioned "a priori" approach to the problem of "lessness". Following the economist's own supply side logic and arriving, 54 years later, in a world with less useful things in it. Deducing from the antecedent axioms of mainstream economics the necessary (because it happened) but avoidable (because it didn’t need to) conclusion- the great collapse. A logic so inescapably simple that, but for the crisis of usefulness and the great collapse, it would otherwise go unnoticed. Some black swans are just too big to see.

To repeat, I'm not so silly as to suggest that useful things are not produced under a supply vs demand model of economics. Or, even that the new enlightened demand models of economics promoted Susan Raworth (Doughnut Economics) and Alex Edman's (Pieconomics) are not useful n their own way. It’s more a question of balance.

How much value in use and how much counter value is being produced by a system at any given time? Whereas, economists are fond of talking about trade offs between incommensurate things, from a value in use perspective, there are trade ups and trade downs within a given system. By converting everything into the single currency of change the equation is one of one of whether a given supply produces (or is more likely to produce) more or less capacity in that system to bring about positive change now or in the future.

In this regard, the difference between economics and modern value theory could not be more clear. Modern value theory argues that all value is that which is useful to life when faced with a crisis. Whereas the pastry economist, Alex Edman’s, persuasively argues that “Pie-economics argues that, in the long run, almost all value becomes financial value”. And he’s horrifyingly right.

Which bring me back to the start.

Losing the Power to Change

Absent useful things we become less powerful or even powerless to change when confronted with crisis. When faced with a crisis it’s not much use reaching for your bulging wallet if there’s no way of buying your way out of it. A sentiment that was ironically captured best by Milton Friedman:

“Only a crisis - actual or perceived - produces real change. When that crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around. That, I believe, is our basic function: to develop alternatives to existing policies, to keep them alive and available until the politically impossible becomes the politically inevitable.”

In the language of modern value theory, the Friedman’s idea is the prime mover responsible for transforming what’s left and lying around into what is right and natural.

Which makes the economic style of reasoning perhaps the most dangerous example of a counter value ever imagined. What the Nobel Laurette failed to imagine is what would happen if all the other ideas died and the one kept alive kept causing the crisis. A prime primer that keeps transforming what left of the world into everything that’s not right with the world.

Not only is the mode of thinking he pioneered not useful in a crisis of usefulness because it it is completely ambivalent to the concept but, when hardwired into the DNA of the modern corporation, tends to shrink everything these prime mover comes into contact with. Everything has become financial value and the only idea that this value can buy is at the root of it all.

By keeping Friedman’s neoclassical legacy alive for so long, what will become politically inevitable will eventually become bio physically impossible. Even if there is a will to change, without useful things, there is simply no power to change. And more urgently given the number of elections this year, it’s worth remembering that the wicked take power by promising it to those who think they have none.

A conclusion that should make understanding how useful things get supplied a global priority. And, if they care about their jobs, on the top of every politician’s to do list.