MC 24: A Vulgar Solution to the Water Diamond Paradox

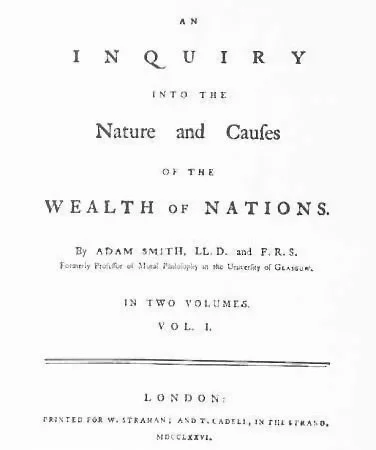

2026 marks the 250th anniversary of The Wealth of Nations and Adam Smith’s water-diamond paradox. Considered among the most foundational puzzles in economics, no theory of value can pass into history without offering up a solution.

Smith described the paradox as follows:

“Nothing is more useful than water: but it will purchase scarcely anything; scarcely anything can be had in exchange for it. A diamond, on the contrary, has scarcely any value in use; but a very great quantity of other goods may frequently be had in exchange for it”

Despite water being among the most useful of all resources and essential for life, water has historically commanded a low price in the market. Diamonds, on the other hand, were considered useless other than as symbols of love, wealth and status. And yet, diamonds fetched the highest of prices.

To try and solve the puzzle, Smith drew a distinction between value in use and value in exchange. But he , along with other classical theorists, were unable to explain why useful water, that required much more labour than diamonds to produce and supply, was still cheap compared to useless diamonds.

The Neo Classical “Break Through”

It was not until the late 19th century that three economists; William Stanley Jevons in Britain, Carl Menger in Austria, and Léon Walras in Switzerland, all came to the same solution- what became the theory of marginal utility.

Marginal utility refers to the additional satisfaction or benefit gained from consuming one more unit of a good or service. Value, by which these economists meant “exchange value” or price” was not determined by total utility but by marginal utility—the utility of the last unit consumed.

For most of the 20th century, clean potable water was abundant and therefore was considered to have low marginal utility. The next glass of water, not adding much to an individual well-being, individuals are not willing to pay much for each additional unit of water.

On the other hand, diamonds being scarce, the mineral is said to have high marginal utility. Because diamonds are rare and the supply is therefore limited, individuals are willing to pay high prices for each additional unit of diamond.

Over the next century, marginal utility has morphed into neo-classical economics. A mashup of marginal utility, scarcity, subjective preference, psychology and production based on a mathematical coefficient of total revenue minus total cost.

The neo classical solution even holding up in the face of climate change. Prices rising as clean fresh water becomes increasing scarce and the demand therefore increases.

The Proto-Classical Solution

About 2250 years before Smith, Aristotle provided a different way to solve the value paradox based on there being only one type of value - value in use

“Of a shoe, for instance, there is both its use to wear and its use as an object of barter; for both are modes of using a shoe”

For hundreds of years, economists have misread this passage as evidence of a difference between value in use and value in exchange. But there was no duality of thought here.

A wanted shoe will be used until worn through. One unwanted shoe will not be used. One hundred unwanted shoes will be used for sale. In each case, there is only value in use and different types of uses depending on whether the shoe is wanted or not.

It is a feature of the market that only unwanted things come up for sale and are exchanged. If a thing is produced that is useful and wanted by the producer it will never come to market. And therefore, the thing with the greatest usefulness will never have a price. Only unwanted things attract a price but this does not mean unwanted things possess “exchange value”. It just means that the best use of that unwanted thing is to lose the use of the unwanted thing.

From a proto classical perspective, it is not because the diamond is scare that the price is high but because:

relative to available and accessible portable water, the money is more useful and therefore wanted. A greater portion of it is kept and not exchanged for water.

but, relative to an individual with abundant money, the diamond is more useful as a symbol of wealth and therefore the money becomes unwanted. It is not kept but the greater portion exchanged for the diamond.

Indeed, the more money an individual has the more unwanted the money becomes. The loss of the money having no discernible impact on the individual the more they are prepared to pay. Price reflecting not the value of a thing to be bought but how little value is placed on money by those who have the most.

It was always a fundamental mistake of the neo-classical economists to think that money was the universal measure of equivalence between water and diamonds. The price was only ever the value in use that the individual put on their money relative to water and diamonds.

What does marginal utility matter if the first unit is not used to do something useful let alone the last? Value, to this economist, means the capacity of a thing to do some form productive work through different modes or forms of use.

Whilst it is true that in a desert water may be scarce. But, in a dessert money and diamonds are useless if the person with the water wants the water. The demand, and therefore the price a thirsty the man or woman is willing to pay, is nothing more than a mirage.

This leads to the other half of the proto classical solution to the water diamond paradox.

For there to be a price, the diamond must also be useless and unwanted by the producer. De Beers must not want the diamonds it mines. If it and all other producers decided to keep their diamonds, there would be no market for diamonds. Instead, being useless to the company, it wants nothing more than to satisfy the urge and even urgency (given the cost of production) to sell them in the market.

In this sense, the price of the diamond is not so much a function of scarcity but the value each producer puts on what they do not want. When the urge to sell unwanted diamonds meets the urge to sell unwanted cash, a price forms. Demand is again, nothng more than a mirage.

But this does not mean that value is generated when two things are exchanged in the markets. It just means that each has substututed their unwant. Value is only generated when De Beers does something useful with the cash and their customer does something useful with the diamond. If the diamond is locked away and never worn, the customer has substuted one unwant for another. Likewise, if De Beers does not use the money to be productive but loses the use to a shareholder, the company has substituted one unwant (diamond) for another unwant(cash) and then substituted that unwant for another unwant (the thanks of the shareholder).

From a proto classical economic perspective, value is best understood as the difference in usefulness between the thing that is unwanted and the thing that is wanted. Put simply, the greater the difference in value in use between something produced that is unwanted, and something useful that is available and accessible and therefore wanted, the more efficient the market exchange becomes and the more value the unwanted thing can generate. This coefficent of the manufactured gradient applies equally to De Beers as it does its wealthy customers.

If the diamond is locked away and never worn, the customer has substuted one unwant for another. Likewise, if De Beers does not use the money to be productive but loses the use to a shareholder, the the company has substituted one unwant for another unwant. Ironically, gross domestic product goes up but De Beers and the individual have gone backward. GDP is a scalar with out any way to tell the direction in which the economy is headed.

God Doesn’t Play Dice with Dookie

Next up in the Millennia Challenge Series I examine the implications of the proto-classical solution to the water-diamond paradox and introduce Says, unspoken second law or number two law.

In the Wealth of Nations Smith had argued that the “propensity to truck, barter, and exchange” was inherent in human nature, but in the following passage Jean Baptiste Say expresses an idea that leads me to conclude that perhaps its more the call of nature at work.

“When the producer has put the finishing hand to his product, he is most anxious to sell it immediately, lest its value should diminish in his hands. Nor is he less anxious to dispose of the money he may get for it; for the value of money is also perishable. But the only way of getting rid of money is in the purchase of some product or other. ”

Though Say, is best known for “Say’s law” or the “law of the market” a classical principle that states the act of production of goods creates its own demand, it seems Say had “discovered” a more viceral second law of economics.

Say’s second law states that the act of producing a good or service that cannot be used by the producer (an “unwant”) creates an overwhelming urge to supply sell that unwanted thing. An immutable law of motion as old as the market, that compels a producer to no less dispatch unwanted products, services and money to the market than a bear is compelled by nature to dispatch it’s sh#t to the woods. And, as I shall argue, governed by the same law of supply.

Make no mistake, I am a vulgar economist. I study economics from the perspective of skat rather than scarcity. Products and services unwanted by the producer being the social equivalent of poo, modern capitalism has become unmistakably an unwinnable gamble of excrement. Something that has no parallel in nature and for good reason. God does not play dice with dookie.

Firms and individuals each producing something use less and unwanted to take the risk that the other has produced something more useful. Each wagering that the insufferable urge to supply and sell their waste or “unwant” will ensure the useless thing flows from where it use less and unwanted across the ambient market to rest where it can be put to best use. What could go wrong?

In MC25 I’ll examine modern economics and Say’s second law from the perspective that what we buy and the money we buy it with have the characteristics of sh$t. Not that this need be a bad thing. Just consider a dung beetle or any number of animals that transform useless poo into useful energy and life. Under the right conditions, useless things want to flow to where they are useful.

But under neo-classical conditions useful a great many wanted things are transformed into useless unwanted things only to be exchanged for useless unwanted things. A real civilization killer.