Since the 1970’s corporate governance academics have arguably had more success in creating problems than solving them.

It started with the agency problem and the challenge to align managers and shareholders. But no sooner had CEO’s received their lucrative options than the next problem arose. CEO’s salaries kept rising and short-termism had become rife. The solution seemed obvious. Boards had become captured by management and what was needed were independent directors. But, being outsiders, many did not recognize that excessive risk was taking capitalism to the edge in 2008. It’s today and we now confront a new crisis and we’ve fallen back into old habits.

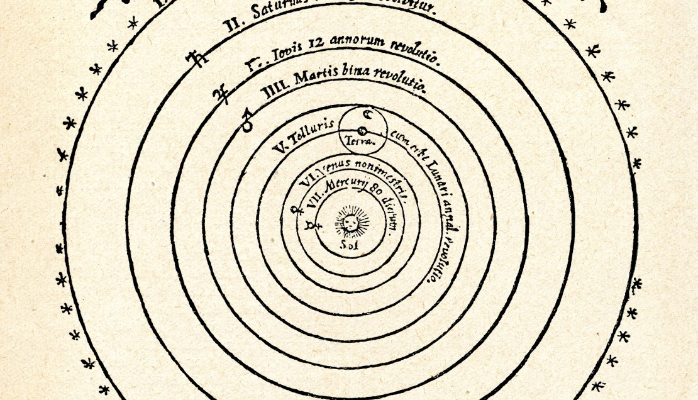

For students of history, a familiar pattern is emerging. In the time before Copernicus:

“Astronomy’s complexity was increasing far more rapidly than its accuracy and that a discrepancy corrected in one place was likely to show up in another.”

Kuhn was commenting on the crisis in Astronomy in 1543, but his description equally applies to the “value crisis” engulfing the world.

Copernicus would of course break the cycle of failure in astronomy by replacing the Earth with the Sun in the center of his universe. This paper argues that humanity is on a similar path, and that only by replacing the shareholder as the organising principle can we begin to fix the problems with capitalism.

Lesson One: Beware Copernican Monsters

In the preface to the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres, Copernicus comments of his contemporaries:

“Nor have they been able thereby to discern or deduce the principal thing – namely the shape of the universe, and the unchangeable symmetry of its parts. Within them it is though an artist were to gather the hands and feet head and other members for his images from diverse models, each part excellently drawn, but not related to a single body, and since they in no way match each other, the result would be a monster and not a man”.

According to Kuhn, Copernicus thought that an appraisal of astronomy in his time showed that the Earth centric approach to the problem of the planets was hopeless. Traditional techniques had and would never solve the puzzle, instead they had produced a monster.

It takes little imagination to see a Copernican Monster lurking within corporate governance codes and guidelines that share no common theoretical foundation other than to persist with a shareholder centric approach to the problem of corporate purpose. But it’s not limited to corporate governance, the pathology extending to corporate sustainability as Goran Janjic reminds us with this info graphic in 2023:

Little has changed since I wrote a decade ago:

“Corporate governance still has no broadly held theoretical base (Tricker, 2009) Instead, it is overwhelmed by multiple and polarizing theories (Letza and Sun, 2002) and though a number of broad or even global theories have been proposed (e.g.Hilb, 2006; Hillman and Dalzeil 2003; Nicholson and Kiel, 2004) none have gained acceptance. Most importantly, agency theory, widely recognized as the dominant theoretical perspective of corporate governance (Durisin and Puzone, 2009) continues to suffer from empirical research unable to validate its claims or accurately predict outcomes (Daily, Dalton and Cannella, 2003). “ *

In much the same way as students of Ptolemy could not accurately predict the movement of the planets, today’s students of the corporation confront the same challenge – a monstrous discipline unable to explain or predict anything other than the crisis we’re in and that another is on its way.

Lesson Two : Avoid Blind Spots

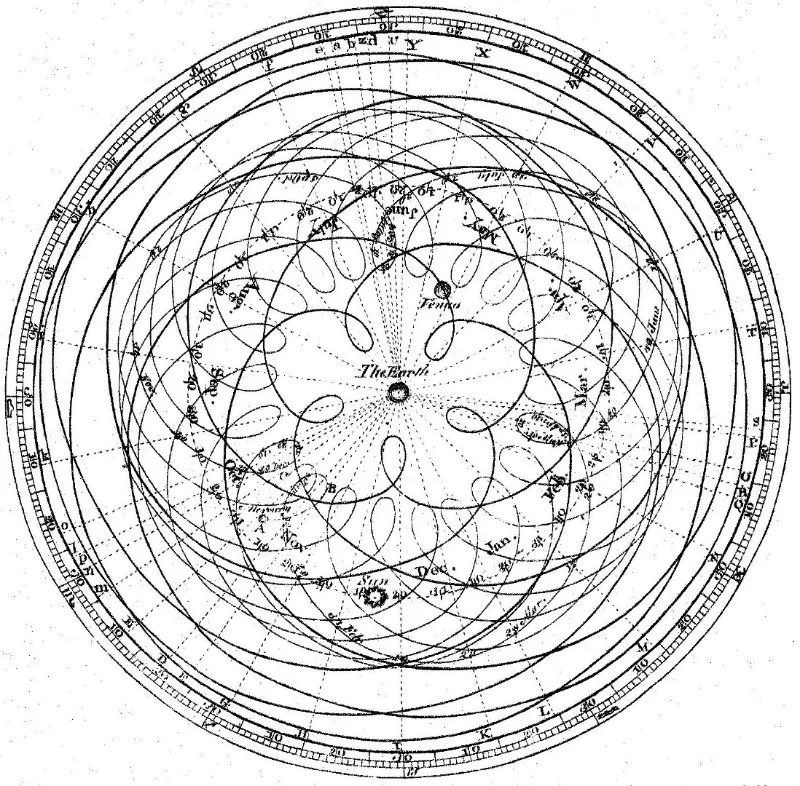

Johannes Kepler, who perfected the laws of planetary motion, understood his discipline's greatest weakness. When questioning why Copernicus had not seen that the planets moved in ellipses rather than circles he responded:

“ Copernicus did not know how rich he was, and tried more to interpret Ptolemy than nature”.

Again, corporate governance suffers a similar blind spot.

Scholars are more likely to interpret Isaac Berle or Merrick Dodd and the shareholder vs stakeholder dilemma than observe how corporations and their directors function in practice.

Since the debate between these two law professors began in the1930’s, the question of corporate purpose has divided into two camps. The first, led by Berle, argues that corporations have a responsibility to maximize shareholder value. The second, led by Dodd, argues that corporations have a responsibility to balance the interests of all stakeholders. These two approaches pull in different directions and compete to be the central blurred focus of corporate governance scholarship and practice.

A debate played out online in 2020 between Professor Lucian Bebchuk of the Harvard Law School (in the role of Berle) and Professor Colin Mayer of Saïd Business School (in the role of Dodd). Impossibly Bebchuk, the scholar whose pinstriped shadow is cast long over the debate, won the day in favour of shareholderism. Watch for your self. A weary world needs more than Mayer’s reasoned hope in humanity and Bebchuk’s reasoned fear of it.

As much as 16th Century astronomers could not see the role of the Sun for the writings of an ancient astronomer, many modern scholars and commentators can’t see anything else for the Bebchuk-Mayer debate. Captured by the shareholder versus stakeholder dichotomy we cannot break the cycle of failure because we can't see beyond these false opposites and the rhetorical traps they set for each other.

Lesson Three : Understand the Power of Attraction

If pre-Copernican astronomy is a metaphor for the problems of corporate governance, does astronomy after Copernicus offer a solution?

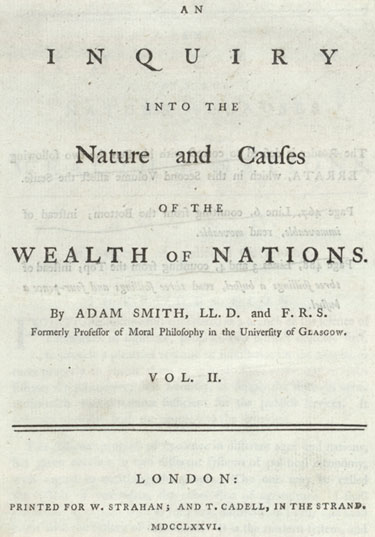

Adam Smith thought so.

Smith was not an economist but a philosopher and, you guessed it, a student of astronomy. Not only did Smith write on the history of astronomy (even using the “invisible hand” metaphor to describe Jupiter), but one of his greatest influence is the man who discovered the laws of planetary motion.

According to Smith, the laws of nature discovered by Isaac Newton could be found in the natural laws of commerce. Smith's concept of the invisible hand was a metaphor for the gravitational force of self-interest:

Is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. [...] Nor is it always the worse for the society that it was no part of it. By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it.

Whereas Newton connected the movements of the planets by “so familiar a principle connection” as gravity, Smith had discovered the equivalent principle of mutual attraction in commerce.

To Adam Smith, the Merchant was to capitalism what the sun was to gravity. In a commercial society “everyman is a merchant” with its own invisible power of attraction. And, according to Smith, the merchant's self- interest and freedom dictate the natural order of commercial society:

It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.

Now compare this explanation to the duty based or deontological theories of Bebchuk and Mayer. Neither the shareholder or stakeholder concept is founded in the idea of self-interest. Instead,they are based in rights and responsibilities owed by the corporation to others. A careful analysis shows that both inverted Smith organising principle and have more in common with the biblical justifications of geo-centrism than anything argued by Smith.

In much the same way as gravity draws the Earth and the sun together, the ethical principle of self-interest drew the merchant and the customer together. Unlike Bebchuk and Mayer, Smith had no time for duties or responsibility. As time has passed, a generation of scholars have forgotten that self interest (rightly understood) and not responsibility was the central organising principle of capitalism.

A principle based on the concept of value is use and symmetrical disequilbrium - in a perfect market organized around the idea of value in use, the ratio in which things are exchanged are determined by symmetrical disequilibrium. Each actor able to use the market to generate value in use by transforming lower quality capitals into higher quality capitals. Sustaining each others existence without that being any part of their purpose.

Unfortunaly we misunderstand what Smith got right, but as I will explain in the next lesson, understand too well what Smith got fundamentally wrong.

Lesson Four : Don't Believe Everything that Adam Smith Wrote

If Smith was right and capitalism was powered by self interest, why is the study of corporate governance so broken and confidence in capitalism collapsing?

The answer is that Smith sabotaged his own incredible idea by claiming that joint stock companies were managing other people's money:

The directors of such [joint-stock] companies, however, being the managers rather of other people's money than of their own, it cannot well be expected, that they should watch over it with the same anxious vigilance with which the partners in a private company frequently watch over their own.... Negligence and profusion, therefore, must always prevail, more or less, in the management of the affairs of such a company.

Smith had inadvertently put the shareholder at the center of capitalism, unaware that he had planted an idea that would fundamentally corrupt his own self organising principle. Not that this was his fault, the joint stock company of Smith’s time was a fundamentally different creature to the 1modern corporation.

There were now two types of merchant. Those who could act in their own best interest and play by the rules of the invisible hand, and those bound to act out of a duty to others. It was as if Newton, having derived his laws of gravitation from the laws of planetary motion, thought it logical for some planets to revolve around the Sun and for others to continue to revolve around the Earth.

A nonsence picked up by Milton Friedman and all those who stood on his shoulders who argue that duty to shareholders comes before the self interest of the corporation. Put another way, unincorporated merchants are free to act in their own self interest but incorporated merchants are under a duty to act in the interests of their shareholders. This is not the free market and it is this flaw that is at the heart of modern "good" corporate governance systems that are destroying capitalism.

In 1856 the law of limited liability wrapped the modern corporation in a Markov blanket only to have it stolen in the 1970’s by the economics inspired by Smith’s mistake.

Which brings me the point where the parallel paths of corporate governance and astronomy cross.

Lesson Five: Progress Loves a Revolution

In the 19th century the marginal theory of value, informed by the first law of thermodynamics led to the revolution in economics, law and corporate governance. The impact of which has triggered waves of crisis. Each larger and more disruptive than the last.

The theory of value that got us in this mess will not be the theory of value that gets us out. A new value revolution is needed.

Informed by modern reformulations of the second law of thermodynamics, a new science of value is emerging based not on the role of money but the capacity of the capitals to do the work of change. A theory that posits that value is a property of many capitals that is transferred to do socially useful work. Marking a return to an objective theory of value that is based not on the work that went into a capital ( Smith, Marx and Ricardo) but the work that the capitals can do. Rightly understood, a corporation’s self interest is to generate socially useful energy in all its forms to power itself and obliquely, all of us.

From a value as work perspective, history tells us that a corporation organized to maximize financial capital will not create the greatest capacity to bring about positive change. If a corporation transforms capitals with a greater value (work capacity) than money into money, the transformation is inefficient and destructive. The result is more money but less value. In practical terms, this means the corporation is producing less capacity to do work in the future for itself and its community of interest. This paradox is at the root of neoclassical economics and the crisis of now. Rather than capitalize resources to create the greatest value, it leads tomore money but less capacity to bring about positive change. A paradox that eventually leads to the value crisis we are experiencing.

You might call it short-termism. Drucker called it suicide:

“Everyone who has worked with American management can testify that the need to satisfy the pension fund manager’s quest for higher earnings next quarter, together with the panicky fear of the raider, constantly pushes top managements toward decisions they know to be costly, if not suicidal, mistakes,”

I call it “decapitalisation”.

Astronomer Eric Chaisson reminds us, “If fusing stars had no energy flowing within them, they would collapse; if plants did not photosynthesize sunlight, they would shrivel up and die; if humans stopped eating, they too would perish”. They’re all capitalists in their own way.

And like these first capitalists, corporations must transfer and transform energy in the forms of the capitals if they are to survive and grow. This process of capitalisation is to corporations what fusion is to our sun, photosynthesis is to plants and metabolism is to humanity. The universal defense against the second law.

All are dissipative open systems, governed by the laws of non equilibrium thermodynamics, that rely on flows of energy to exist and grow. The twist in the story is that like the sun and plants, corporations too serve a social purpose despite having no conscience or awareness of duty or responsibility. Serving humanity obliquely by transferring and transforming energy and passing it on in more socially useful forms.

Through the lens of value as work, corporations are a form of incorporeal motor. A prime mover that when governed in the best interests of the entity itself, optimises the transformation of capitals to generate the greatest social energy or value. Creating value on an industrial scale by transforming capitals with lesser concentrations of value into those with higher - social, human and intellectual capital. The modern corporation, conceived as a thermodynamic entity, is capable of doing for socially useful energy what wind and solar does for physical forms of energy.

But today many of these motors run in reverse. Transforming the most valuable capitals into the least valuable to satiate the shareholders desire for financial capital. Neo-classical economists, having ignored the second law of thermodynamics for a century, had turned corporations into energy sinks when they are intended to be energy generators. Put simply, by requiring that corporations maximise shareholder value, corporations ceased to capitalise and thus ceased to be capitalist in the true sense of the word. When corporation consume more value (defined in terms of socially useful energy) than they create, corporations start decapitalising everything to the point of collapse. The shareholder primacy concept is nothing short of fools alchemy.

The solution to the more money less value paradox is a Copernican style revolution.

What 1553 can teach us now is that the answer to the crisis in capitalism is as close as the warmth of the sun on our face. Substitute the independent corporation for the shareholder at the centre of capitalism and, using the new science of value, power these creatures of statute with innovative value generators. Sun like entities that transform socially useful energy and draw in their communities of re-inforcing self interest, like planets under the power of attraction. And like the sun, supply value to empower us all.

Post Script

Following comments on Linkedin I’ve added this post script

Lesson Six : Truth Doesn’t Go Viral

Copernican heliocentrism took near a century to be taken seriously by the academic community (and geocentrism was still being taught in the 1700's). Galileo provided the observations and Newton and Kepler the math to convince the only profession more sceptical of science than the law, religion.

Galileo before the Holy Office by Joseph-Nicolas Robert-Fleury

Then it was Catholic Church. Now, it's economics and mathematics.

The big difference is that the priests didn't lose their jobs. Catholicism eventualy being flexible enough to accomodate new ideas. Galileo prescient when he said that the truths of scripture, when properly understood, do not conflict with the truths of science. The problem is that the truths of the new theory of value represent an existential crisis for economics.

It’s no exageration to say that the Catholic Church is more open to accepting the possibility of alien life existing in the universe, than neo classical economists are to accepting the possibility that corporations exist in a meaningful sense and therefore have their own interests in creating capitals other than money. Ne0-classical economics is founded on the dualism of a subjective theory of value and the non-entity premise - the idea that corporations are fictions. Without that premise their maths doesn’t add up and like Ptolemy, Milton Friedman and a thousand PhD’s would become unemployed. There are no jobs on the wrong side of history.

The problem is that the climate did not change, species did not dissapear and humanity’s youth did not dispair because of the crisis in 1543 . The belligerent astonomer was only a harm to himself. His mistaken beliefs did not change the solar system. If only that was the case for the economists. Economics is performative. Its pathogenic influence baked into nearly every institution with barely a whisper of its potential to cause deadly harm if followed.

The sixth lesson is not to assume that the truth will go viral. And that’s no accident of history.