Duty Before Virtue : The Real Ethical Dilemma Facing Corporate Governance

What holds corporations and their stakeholders together - duty or self interest?

Paul Polman, CEO of Unilever NV, considers himself a hardcore capitalist. A label many in the corporate governance community find hard to believe given his stance against the mantra of maximizing shareholder value:

“I don’t think our duty is to put shareholders first. I say the opposite”.

The Dutchman is convinced that something is rotten:

“Capitalism in its current form is broken... The very essence of capitalism is under threat as business is now seen as a personal wealth accumulator…. if you go back to Adam Smith, his thoughts were that capitalism was intended for the greater good”.

Since Polman's appointment, the Anglo-Dutch company has ended quarterly reporting, refused to pander to analysts, doubled capital spending, increased R&D, reduced the number of hedge funds in its shareholder base by half and, according to its CEO treats people, such as their 75,000 small hold tea farmers, fairly.

Polman’s approach puts him at odds with elite academics like Professor Macey from Yale Law School who teaches that “all major decisions of the corporation, such as compensation policy, new investments, dividend policy, strategic direction and corporate strategy should be made with only the interests of shareholders in mind”.

To his critics, Unilever has an impostor at the helm. But this CEO is no phony.

THE ETHICS OF THE INVISIBLE HAND

Capitalism is founded on the ethics of self interest rightly understood. Summed up in the metaphor of an invisible hand.

Adam Smith formulated the most basic organizing principle of capitalism – In a commercial society “everyman is a merchant” . And the merchant's self interest and freedom dictates everything from price to the nation's progress.

It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.

The Scotsman argued that self-interest (but not selfishness) produces the greatest good. To Smith the “everyman merchant”:

Is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. [...] Nor is it always the worse for the society that it was no part of it. By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it.

It is important to remember that Smith was neither an economist or an accountant. He was a moral philosopher. More importantly, Smith's moral compass wasn't the duty to serve shareholders or society. Rather, his north was individual prudence, temperance, justice and courage. Qualities that transform greed and avarice into self interest rightly understood.

At the core of Smith’s formulation of capitalism was virtue ethics that yielded wealth for both the individual and the nation.

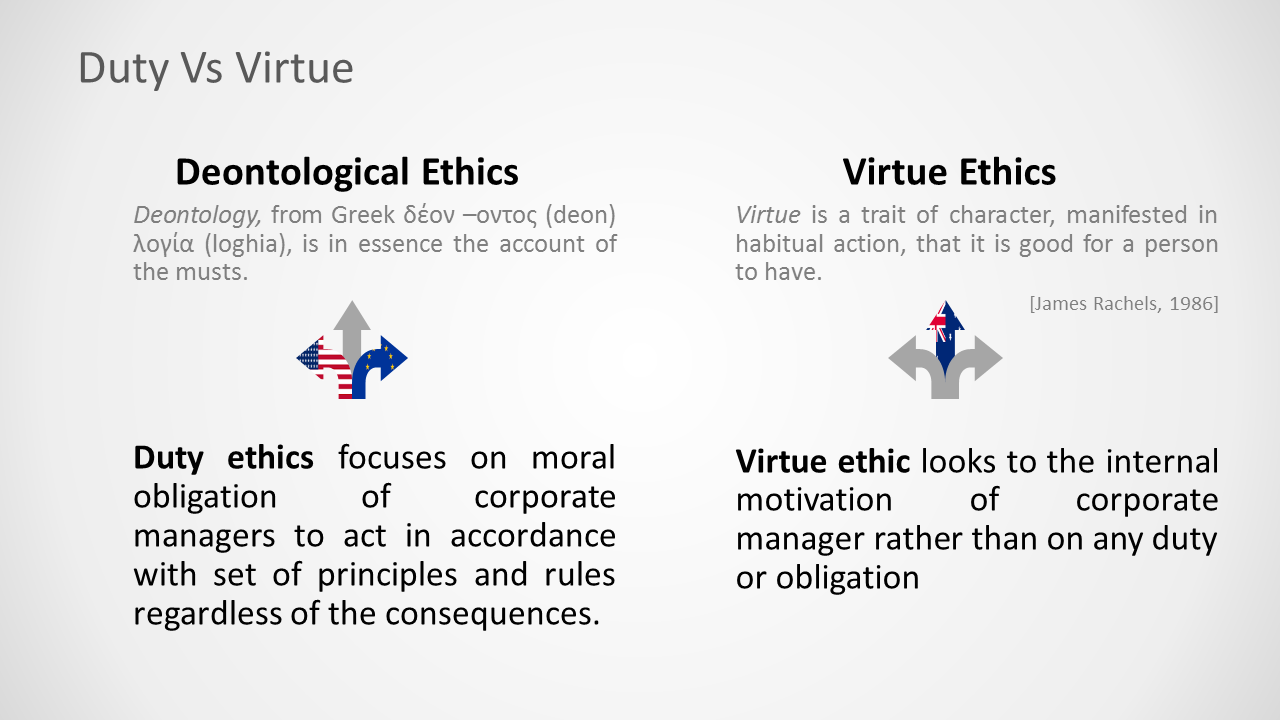

Virtue ethics are concerned with the moral character of the person carrying out an action, rather than any ethical duties and rules.

What makes the invisible hand a virtue ethic is that a persons actions are not motivated by obligations or duties, but by an internal motivation directed at realizing a person's self interest rightly understood.

Nowhere was this spirit more embraced that in the young United States. When Alexis de Tocqueville returned from his travels he provided this remarkable insight?

inhabitants of the United States almost always manage to combine their own advantage with that of their fellow citizens; my present purpose is to point out the general rule that enables them to do so. In the United States hardly anybody talks of the beauty of virtue, but they maintain that virtue is useful and prove it every day. The American moralists do not profess that men ought to sacrifice themselves for their fellow creatures because it is noble to make such sacrifices, but they boldly aver that such sacrifices are as necessary to him who imposes them upon himself as to him for whose sake they are made.

The unfettered pursuit of money did not drive the free market. The invisible internal combustion engine of capitalism was a commitment to freedom and educated self interest. A limitless supply of fuel to power America's growth as a nation and economic powerhouse.

But, then something happened.

Toward the end of the last century progress stalled, the public company became endangered and confidence collapsed in the economic system that had improved the living standards for so many.

Smith's engine had been stolen and replaced with a poor substitute. No longer was capitalism powered by self interest, from then on capitalism would be powered by duty.

HOW MILTON FRIEDMAN BROKE CAPITALISM

The thief was the one person that no one would ever suspect - the twentieth century's most prominent advocate of "free" markets.

When Milton Friedman declared in his 1970 New York Times article that "the social responsibility of business is to increase its profits" he wasn't channeling the ethics of Adam Smith, but those of Moses and the 10 commandments.

His was a duty ethic.

Duty ethics, also known as "obligation", "rule" or "deontological" ethics, states that we are morally obligated to act in accordance with a certain set of principles and rules regardless of outcome.

What no one in charge seems to have noticed is that the Professor had switched duty ethics for virtue ethics as the moral foundation of capitalism. For the Nobel prize winner, a corporation acted ethically when it maximizes shareholder value within the constraints of the law. In his view, any other obligation should be met with the kind of outrage reserved for social deviance.

From then on, Smith's most famous quote would read:

It is not from the self interest of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that shareholders expect their dinner, but from their regard to their duty and responsibility.

But what Friedman and his coterie of economists and lawyers didn't understand is that they'd introduce a terrible mischief into the free market by insisting that corporations act out of duty rather than self interest.

For the invisible hand, and therefore capitalism to work, corporations needed to be free to act in their own best interest too. In a free market system, the needs of the shareholder are satisfied out of the needs of the corporation. The shareholder’s share of wealth created by the corporation is commensurate to the needs of that corporation, not the needs of shareholder. More importantly, a corporation should be free to elevate the priority of any other stakeholder if that was in its interest.

However, under the norms of shareholder primacy promoted by Friedman and others corporations are not free. They are misconceived as property to be used to enrich other people. Whereas, directors and managers are not the corporation's agents but the shareholders. "Good governance" is not an expression of freedom but a form of corporate servitude that corrupts the free market.

To call Friedman's version of duty based capitalism the "free market" is doublespeak. Something Unilever's CEO isn't afraid to call out “I’m not just working for them.” “Slavery was abolished a long time ago.”

In a truly free market, corporations are free to chose self interested self denial.

The single most important act in producing the common wealth is the willingness to sacrifice a portion of profit for a rarer treasure.

But under the conditions of duty based capitalism, there is no self denial at the expense of the shareholder. Profits are to be maximized regardless of the consequence - duty pollutes. For this is a feature and criticism of duty based ethics. Morality is judged not by the consequences, no matter how terrible for people, planet or even the corporation over the long run, but on the basis that the duty is followed.

Duty excuses every sin of efficiency in pursuit of profit.

This is not free market capitalism, it is an institutionalized form of rent seeking that threatens capitalism. Neither Smith or de Tocqueville would recognize the champions of shareholder wealth maximization as true capitalists.

Duty Before virtue

To understand the difference between Friedman's duty ethics and Smith' virtue ethics consider the decision by companies to use "cheap" money to buy back over valued shares.

Since 2008, US public companies have gone on what some describe as a buy back binge. Over the past 3 years S&P 500 companies have spent more than $1.5 trillion dollars in repurchasing their own shares. A trend that is expected to continue unabated in 2016:

Of the $2.2 trillion in cash corporate America is poised to spend next year, roughly half will go directly to shareholders. Between stock buybacks and dividend increases, Goldman Sachs estimates that just over $1 trillion will end up flowing to shareholders, a 7 percent increase over 2015.

To put that in simple terms. American corporations will spend as much money deliberately tearing up their own shares as they will on research and development, capital expenditure, remunerating their employees, paying their suppliers and building their brands. To a virtue capitalist, there could only be one thing more perverse, borrowing money to pay for the privilege of buying the one thing that corporations have a virtually unlimited supply of - their own shares.

The current US corporate debt situation is spelled out in this note from Goldman Sachs:

Companies in the United States have taken advantage of low interest rates to issue record levels of debt over the past few years to fund buybacks and M&A. This has driven the total amount of debt on balance sheets to more than double pre-crisis levels"

But it's not just debt. Debt comes with onerous covenants, billions in interest payments and the risk that comes with having to earn the money to pay it back. Corporations are rewarding their shareholder by destroying themselves. The corporate equivalent of Cotard's Syndrome.

Share buy backs are the logical extension of Friedman's duty based ethics. Directors are morally obligated to reward shareholders despite the absence of any meaningful benefit to the corporation. Rather than save or use than money in ways that support the viability of the corporation, the money is essentially given away three times. First to the shareholder and then, through interest payments to their lenders and finally when the debt is repaid.

Adam Smith had no time for rent seekers.

The virtue of self interest rightly understood is that each stakeholder is remunerated according to their contribution to the viability of the corporation. Share buy backs without a commensurate benefit to the corporation, would be unquestionably immoral. let alone taking on debt and covenants to do so. Under Smith's version of capitalism, if shares are repurchased it's because that strategy serves the interests of the corporation, not its members.

Indeed, much of what is considered moral through the lens of duty ethics looks decidedly immoral through the lens of virtue ethics.

To Friedman's followers, directors have a duty to maximize profits by minimizing tax, reducing costs and distributing the resulting profits. To Smith's followers, it is in the corporation's self interest rightly understood to have a real cost base (including paying a stable rate tax), to spend money on things that are worth more than money: intellectual property, human capability and social license (to name only a few) and to distribute profits wisely. To stop short term thinking, all corporations must do is stop acting out of a false sense of duty.

Cutting the bonds of corporate servitude

What Unilever and its leader know is the duty to maximize shareholder value is a broken moral compass.

The Guardian newspaper sums it up well:

Polman is scathing of companies that claim their hands are tied by fiduciary duty to maximise profits for shareholders in the short-term, arguing that this is too narrow a model of Milton Friedman's old thinking. The world has moved on and these people need to broaden their education with the reality of today's world.

But he’s far from alone in demanding change.

Leading the charge to expose the myths of shareholder primacy is Distinguished Professor Lynn Stout of Cornell Law School. According to Stout:

"What shareholders own are shares, a type of contract between the shareholder and the legal entity that gives shareholders limited legal rights. In this regard, shareholders stand on equal footing with the corporation’s bondholders, suppliers, and employees, all of whom also enter contracts with the firm that give them limited legal rights"

Stout systematically deconstructs the shareholder value norm to reveal that it is not supported in law or fact. According to the professor, under the influence of shareholder primacy shareholders are suffering their worst investment returns since the 1920’s. Life expectancy of Fortune 500 firms has reduced over the past century from 75 to 15 years (now 10 years) and the number of publicly-listed companies has almost halved.

While the the explosion in buy backs and debt might suggest that no one's listening to the Professor, the looting might also signal that investors know the good times are coming to an end.

Late last year, European law makers made a decision to recognize that shareholders do not own corporations. Paige Morrow, from law firm Frank Bold explains:

The directive will explicitly acknowledge that shareholders do not own corporations - a first in EU law. Contrary to the popular understanding, public companies have legal personhood and are not owned by their investors. The position of shareholders is similar to that of bondholders, creditors and employees, all of whom have contractual relationships with companies, but do not own them.

This tiny recognition signals the end for duty based capitalism.

If corporations are separate distinct and sovereign persons, Friedman's moral duty to enrich their imaginary owners is exposed for what it always was - the vision statement on the desk of every fund managers desk. An unlikely commercial strategy that had turned the whole of capitalism into a business model run by investors. Any industry that's clever enough to steal capitalism's mojo without anyone noticing, is smart enough to know when it's time to empty the coffers and start looking for a new business model.

A RETURN TO VIRTUE ETHICS

Paul Polman is bringing ethics back.

“if you are single-mindedly focused on one value driver you will not be successful. If you only focus on being sustainable, it would be wrong. If you focused just on shareholder value maximization that would be wrong. The challenge in the new world is to balance it all”.

Freed from the tyranny of duty and, with corporate personhood restored, capitalism's true source of power can be restored. But not everywhere.

According to the chief justice of the Delaware Supreme Court , duty ethics are the law. Not so in Australia and other commonwealth and continental jurisdictions. The law of purpose in Australia is founded on personhood and virtue ethics:

A director or other officer of a corporation must exercise their powers and discharge their duties in good faith in the best interests of the corporation

It's not about putting shareholders first (or second for that matter). Nor, as Roger Martin and others argue, is it about putting customers first. It’s not even about putting employees, the environment or any other stakeholder first. The free market has always been about the virtue of pursuing a deep and profound understanding of a person's self- interest.

A virtue that reaches its full expression through the modern corporation as a separate and distinct legal person. Profit, was never a synonym for a sovereign corporation's interest. Something regulators, academics and business leaders will discover for the greater good of us all.

My proposition is that the central object in capitalism is the concept of personhood biological and corporate. Each a Smithian merchant in their own right having an innate inclination to continue to exist and enhance itself by aligning its self interest with the self interest of other merchants.

But what does a corporation's interest look like?

In the case of a corporation, an interest is one of the capitals - human, intellectual, environmental, social, produced and financial. Commonly associated with Integrated Reporting <IR>, the capitals can equally be flipped to provided a complimentary accounting to explain how corporations maintain their existence.

I'm working on a theory that to exist a corporation must accumulate, convert and exchange each of the capitals to maintain and enhance existence or >i<.

>i< is based on the intrinsic interests of the corporation and not the extrinsic interests of shareholders or stakeholders. It's derived from a non teleological or purpose based understanding of corporate existence.

The basic proposition underlying >i< is that excess and lower value capitals (typically financial capital) must be converted by a corporation into rarer and higher non financial forms of capital (human, intellectual, social capital etc). The purpose of this is to enable the production of lower forms of capital (produced capital) which in turn must then be converted into financial capital which is then converted into rarer and higher forms of capital and on it goes.

The key to >i< is that the capitals are not measured in dollars but a universal measure of equivalence or units of value. The objective is to capitalize - that is to accumulate, convert and exchange capitals to produce the greatest net number of units of value (while at the same time having sufficient financial capital to pay debts as and when they're due).

Theoretically this cycle of capitalisation can continue into perpetuity provided the corporation does not exploit the sources of capital or do something stupid. And by so doing, the corporation obliquely serves the interest of all those who hold capitals. [A paper and model that explains the concept of C will be published soon].

The problem with Milton Friedman's duty ethics is that it corrupts this process by exhausting the capitals rather than creating them. Under the influence of shareholder primacy the corporation begins to convert its higher capitals human capital, intellectual capital, social capital etc into one of lowest forms of capital - financial capital. It's called "efficiency" and "Costing Out". The resulting financial capital is then transferred for limited or no capital return in the form of buy backs, dividends etc. If there is any doubt about this process total payout to shareholders in US as a percentage of net income of the corporation stands at unprecedented levels.

We call this short-termism. Drucker called it suicide:

“Everyone who has worked with American management can testify that the need to satisfy the pension fund manager’s quest for higher earnings next quarter, together with the panicky fear of the raider, constantly pushes top managements toward decisions they know to be costly, if not suicidal, mistakes,”

I call it decapitalization.

Friedman's duty engine exhausts the corporations energy previously stored across all the capitals making it less able to maintain its existence. If the process is allowed to continue, the corporation's value previously stored across all the capitals becomes exhausted. Ultimately making the corporation less able to maintain its very existence. This process is the corporate equivalent of Cotard's syndrome. And, if the decline in the number of public companies and confidence in capitalism are any measures, its become a pandemic.

But what does a return to virtue based capitalism mean for shareholders?

Under this new norm of governance, shareholders needs are prioritized alongside all other stakeholders according to their contribution to strength and viability over the longest time. As Unilever's CEO notes, the dividend is part of “balancing the choices to multiple stakeholders” . He's right. Shareholder's will continue to receive a return. But soon they'll have to get their dinner just like everyone else.